Employees or investors?

We must be wary of making definitive, eternal statements in a world of uncertainty and change.

By Dominique Jacquet

In this June’s vidcast, I talk about the spectacular IPO of Snowflake, which was worth 120 years of revenue at the end of its first day of listing, without there being any question of realizing, in the short term , the lesser profit.

Since then, the market has become “wiser” and the firm is worth “only” 20 years of revenue and 500 years of EBITDA, knowing that operating losses represent, in 2022, 41% of sales. We are back in a situation described as “normal”…

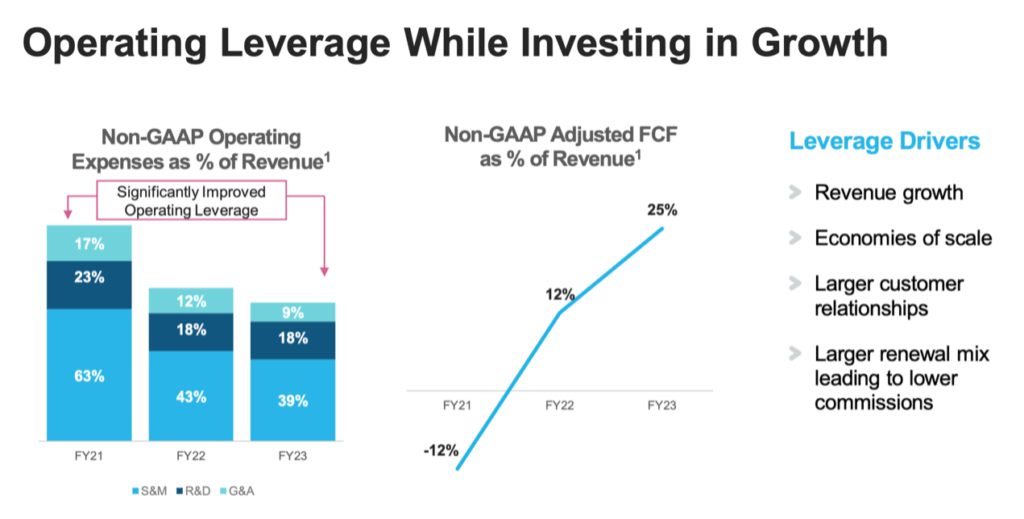

What seems interesting to me is the firm’s eagerness, in its financial communication, to explain that the real profitability of Snowflake is not observed in its accounting result calculated and presented according to the standards in force (GAAP), but in the “non-GAAP” earnings and free cash flow. Why “adjust” accounting standards? Because they do not reflect the economic reality of the company. Therefore, for the investor to receive relevant information, it is necessary to derogate from the Rule (GAAP) and produce non-standard accounts (non-GAAP).

The accounting regulatory authorities assert that these remunerations correspond to remuneration of employees and that, as “quasi-wages”, they must be treated as such in accounting terms and appear as expenses in the income statement.

The debate is lively, for or against expense recognition.

The argument in favor of recognition is rather dictated by common sense and reflects a conception of the employee of a firm as belonging to the category of stakeholders and being remunerated for his/her contribution to the activity. The nature of the remuneration would not matter.

In fact, it matters a lot.

The famous Agency Theory has accustomed us to speeches which present voracious employees and who implement all their skill to divert for their benefit as much as possible of a wealth which, in all legitimacy, would return to the shareholders. It is a culture of conflict. In order to align the interests of managers (group extended to key employees) and shareholders, we imagine all kinds of constraints. For example, indebting the firm means limiting the cash entrusted to managers and of which they will certainly make questionable use, such as launching a costly acquisition to increase their prestige to the detriment of the creation of value. Let’s be honest, it’s clear that it happened… So, compensating employees with RSUs or options means allowing them to benefit from the increase in equity value (listed company or not), therefore aligning their financial interests with those of the shareholders. The tool is intellectually based on the conflict, but appears more like a motivation than a constraint.

I would like to propose a managerial and financial reflection based on a different interpretation of the relationship between employees and shareholders.

Suppose you are offered a job in a promising company, where you believe the management is of high quality, the choices are the right ones and the potential is immense. You are attracted to the company not only as an employee, but also as an investor. How to invest? The proposed salary is equal to 100 per week. Accepting to receive a salary of, say, 80 and get RSUs and options for a value of 20 is about the same as working Monday through Thursday to receive an income and Friday to invest in the firm. You buy an option (or a RSU) by paying for the investment through your work. It is exchanging labor for capital and not “opposing” the two economic actors.

When a company issues Equity Warrants, investors pay an amount to buy the financial security. The price paid appears in the shareholders’ equity and as an asset in cash. It would be ridiculous to account for the purchase of stocks as expenses in the P&L. When an employee, a key employee of the firm, decides to invest in the company, why would his/her investment be treated differently? The security appears in equity and the positive impact on cash is to be found in the non-payment of a salary (then saving a cash outflow).

This perspective does not present a conflictual relationship between employees and shareholders, but on the contrary shows that one can be, in one’s own economic approach, both employee and investor. This perspective is built in an environment of cooperation between the different actors who act in an environment that favors the community over the individual, cooperation over conflict, positive-sum game over zero-sum game and trust over distrust.

An article published (May 2003) in the Harvard Business Review by eminent scholars, Zvi Bodie, Robert Kaplan and Robert Merton (Nobel Prize winner), carries its conclusion forcefully and with a hint of annoyance in its title: For the Last Time: Stock Options Are an Expense.

A sort of End of History, as Francis Fukuyama so aptly suggested in the book he published in 1992 following the fall of the Berlin Wall.

This statement is only “true” in a very specific cultural context, a context of conflict between two strongly divided populations. Other interpretations and contexts may lead to a more nuanced answer… and one should be wary of definitive and eternal assertions in a world of uncertainty and change.