Is Complexity Beautiful

The growth resilience of Nestle questions 20 years of category management

By Ivan Cuesta

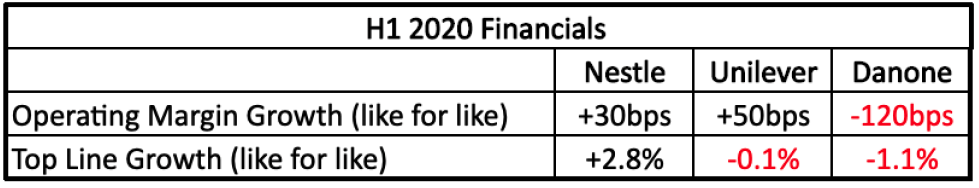

The first semester 2020 of the FMCG industry, despite the global and transversal impact of the Covid 19, has shown different financial performance among industry leaders.

Indeed, Unilever delivered a negative top-line growth of (0.1%) with positive margin development. Danone provided a negative growth of (1.1%) and negative margin development while Nestle reported a positive growth of 2.8% and positive margin development.

Why do we see such differences?

For the last 20 years, the industry trend is to focus on a few “high growth high margin categories,” reinforcing companies’ values on healthier nutrition, better sustainability, etc.

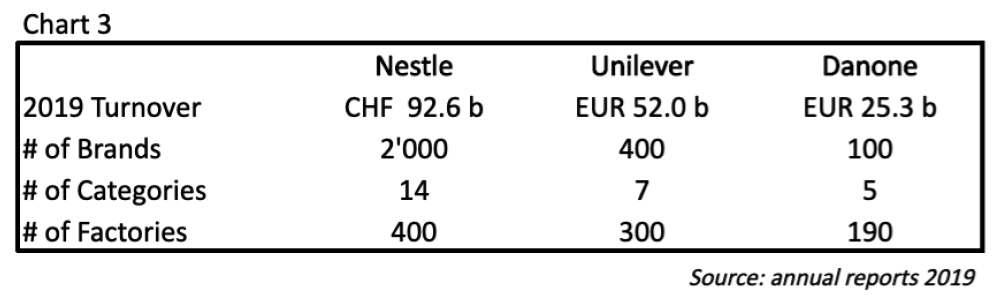

In the case of Danone, this trend has been translated into getting rid off of beer, candies, biscuits, cold meat, and epicerie categories to focus on dairy, plant base, water, infant, and medical nutrition. These 5 categories represent around 100 brands and are managed by 3 business divisions, of which 2 have reported significant negative growth in Q2.

Unilever also jumped on the same boat, focusing on home and personal care, as well as on food categories, for the equivalent of 400 brands. The significant pressure on food and personal care has been compensated by the home care segment’s strong performances.

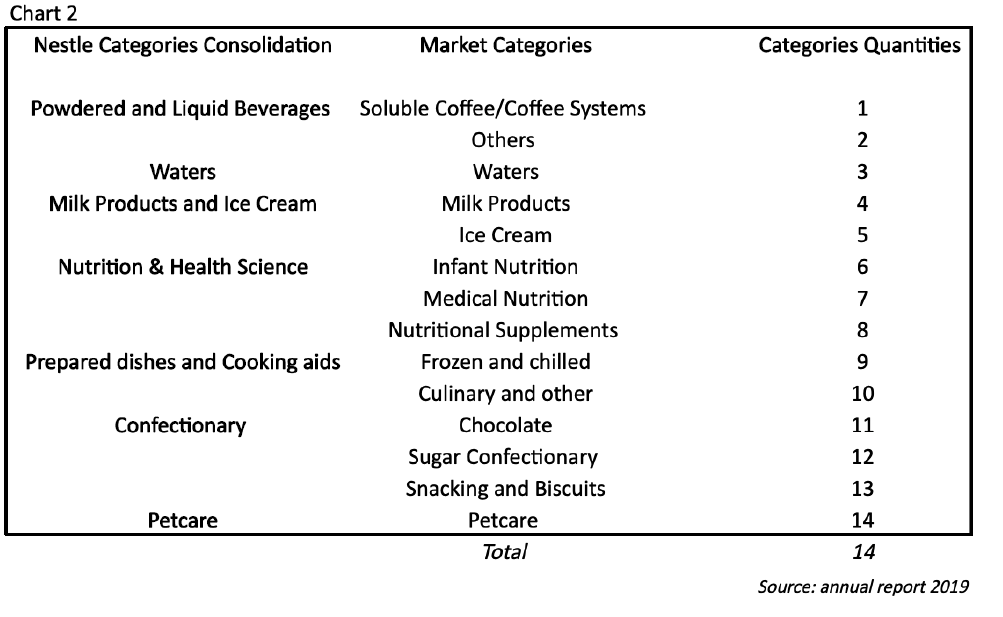

Nestle initiated a similar portfolio adjustment under the leadership of Peter Brabeck, and it is accelerating with the current CEO Mark Schneider. Even though Nestle reports 7 consolidated categories, in reality, they run 2’000 brands out of 14 different categories (chart 2), of which “half of them sits outside” the industry trend according to their activist shareholder Third Point.

This apparent complexity, compared with peers, (chart3) is currently showing a unique resilience that competitors and the current management of Nestle might meditate on. Indeed, despite the long term decision taken by Nestle’s management after the WW2 to enter into cosmetics to mitigate portfolio’s risks, the company recently divested Galderma and officially sticks to the portfolio adjustments initiated by Peter Brabeck.

If this resilience becomes an asset in uncertain times, the Nestle’s old philosophy, “we can exit a brand, not a category,” might come back. If that happens, Danone should remember the strategy of Antoine Riboud, to represent 40% of shelves of its retail customers across many different categories.

It seems that financial markets are valuing Nestle’s unsinkable resilience as the market capitalization is at its highest level ever. In comparison, respectively, Danone and Unilever are 30% and 15% below their highest stock value in 2019.

Is diversification going to balance the category focus? Is diversification, currently defined as

complexity, becoming beautiful again?